BLOOMBERG: TRUMP TAX CUTS ARE WHY US BOND YIELDS AREN'T HIGHER

The government’s fiscal policies amount to robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield has risen 49 basis points since the beginning of the year to 2.90 percent, and the 30-year bond yield has jumped 33 basis points to 3.07 percent. Given all the talk about:

- The strong economy,

- The Federal Reserve raising interest rates,

- $1 trillion federal budget deficits and

- Increased government borrowing,

... why aren’t yields even higher? Blame the tax cuts.

Despite data showing that gross domestic product grew at a 4.1 percent annual rate last quarter, most forecasters expect the resulting huge federal deficits and Treasury borrowing to pay for the lost revenue from reduced corporate taxes to slow growth. They look for annual real GDP growth of no more than 2 percent longer term as retiring postwar babies and limited immigration retard labor-force growth and curb productivity, which is running only 0.7 percent on average this decade.

Plus, much of the $1.5 trillion in tax cuts over 10 years is likely to be saved, not spent, by consumers and businesses, money that either directly or indirectly ends up buying those newly issued Treasuries. It’s robbing Peter to pay Paul. It’s already happening. Newly and dramatically revised government data show that between February 2013 and this June, the household savings rate jumped from 5.8 percent to 6.8 percent. That’s a total increase in savings of $1.6 trillion. What a contrast with the old numbers that had the savings rate dropping from 4.7 percent in February 2013 to 3.2 percent in May.

The drop in the maximum U.S. corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent means many companies have money to burn — or invest in Treasuries, among other options. They’re certainly not plowing it into plant and equipment spending. New orders for non-defense capital goods excluding aircraft, a harbinger of capital spending, are decelerating. They rose just 0.2 percent in June from May, down from 2.8 percent last December versus November.

The growth in U.S. bank commercial and industrial loans has plummeted from 13.4 percent year over year in January 2015 to 5.8 percent last month. The rate of growth in commercial bank assets is decelerating and would be even weaker except for the surge in their holdings of Treasuries and other government-related debt. In the past three months, they added $59.1 billion of the debt, bringing total holdings to $2.57 trillion, according to Fed data.

The latest Fed survey of senior loan officers found demand for commercial and industrial loans among big borrowers continues to be flat, extending a three-year-long trend. Also, commercial real estate loan demand remains weak while there are actual declines in auto loans.

The new tax law encourages U.S. multinationals to repatriate the $3.1 trillion they held abroad. Although some of that money was already invested in Treasuries and other U.S. investments, more is being returned and invested in these instruments. With plenty of money, U.S. corporations are also slashing their stock and bond issuance. According to the Fed, the amount raised from such activities fell 18 percent to $882 billion in the first half of 2018 from $1.08 trillion in the same period of 2017.

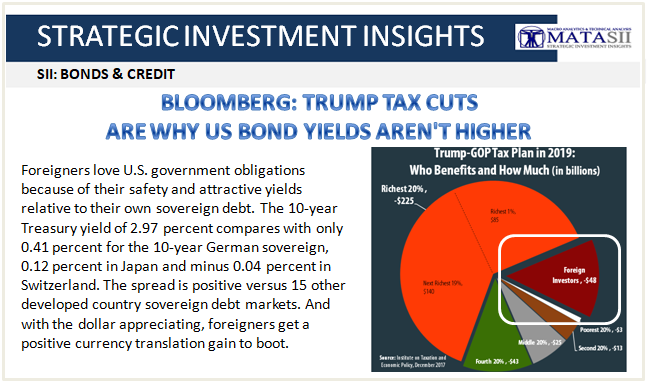

Don’t forget that foreigners love U.S. government obligations because of their safety and attractive yields relative to their own sovereign debt. The 10-year Treasury yield of 2.97 percent compares with only 0.41 percent for the 10-year German sovereign, 0.12 percent in Japan and minus 0.04 percent in Switzerland. The spread is positive versus 15 other developed country sovereign debt markets. And with the dollar appreciating, foreigners get a positive currency translation gain to boot.

Longer-term Treasuries are also benefiting from the uncertainty over the escalating foreign trade wars. Despite initially higher prices for goods due to tariffs, the final result is likely to slower economic growth and deflation, which support Treasury bond prices.

What about the Fed’s rate increases? The further out the yield curve, the less that Fed action affects yields. Our analysis reveals that over the entire post-World War II era, a 100-basis-point rise in the federal funds rate resulted, on average, in a 44-basis point hike in the 10-year Treasury note yield but only a 24-basis point rise in the 30-year bond yield. Other forces, notably inflation, dominate in the further-out years.

There’s plenty of potential demand for longer-term Treasuries if the bearish speculators get squeezed. There are now a record 590,000 contracts betting on higher 10-year Treasury yields. That may be disappointed.