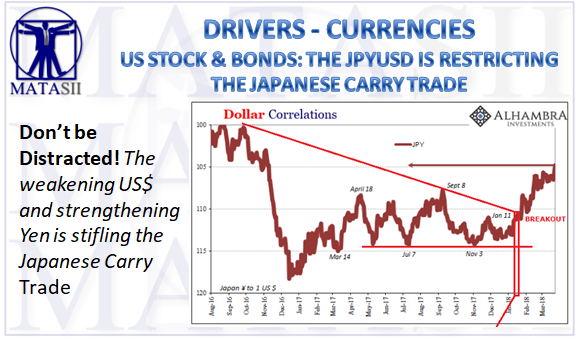

US STOCK & BONDS: THE JPYUSD IS RESTRICTING THE JAPANESE CARRY TRADE

REMEMBERING THESE PREVIOUS POSTS AT MATASII

DOLLAR SWAPS STATUS SHOWS WHAT IS GOING ON - EURODOLLAR CHANGE DUE TO JAPAN'S ABSENCE

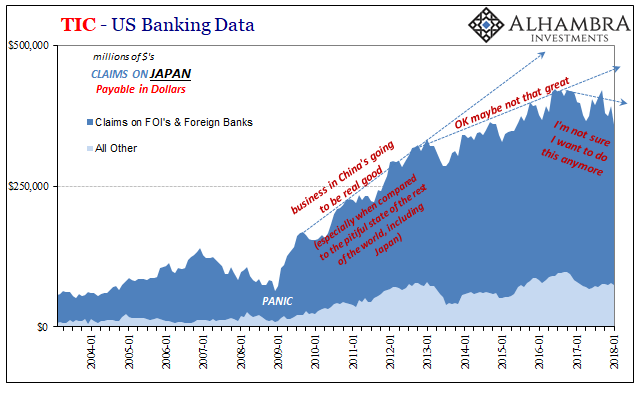

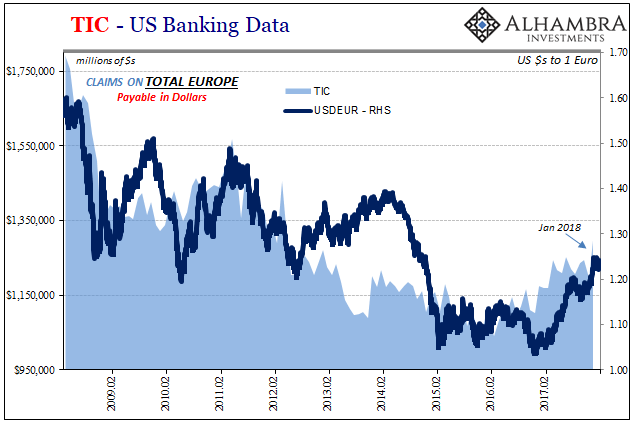

Inflation hysteria in some places hasn’t just faded, it has disappeared almost entirely. The old saying is that shooting stars burn out the fastest. One of the hottest systems was in Europe. The ECB, we were told, had done it. Even though QE hadn’t achieved anything of substance in its first or second year, the third was apparently the charm. It led to rife speculation earlier this year about not just tapering QE but even rate hikes to rival the Fed’s.

Not so much anymore. The problem is, still, inflation. In a lot of ways, the frenzied mainstream assessment about price increases was just that. It took relatively minor improvements in data and market prices and blew them all out of proportion (for largely political reasons rather than rational analysis). At the top of this list of raw hype was inflation expectations.

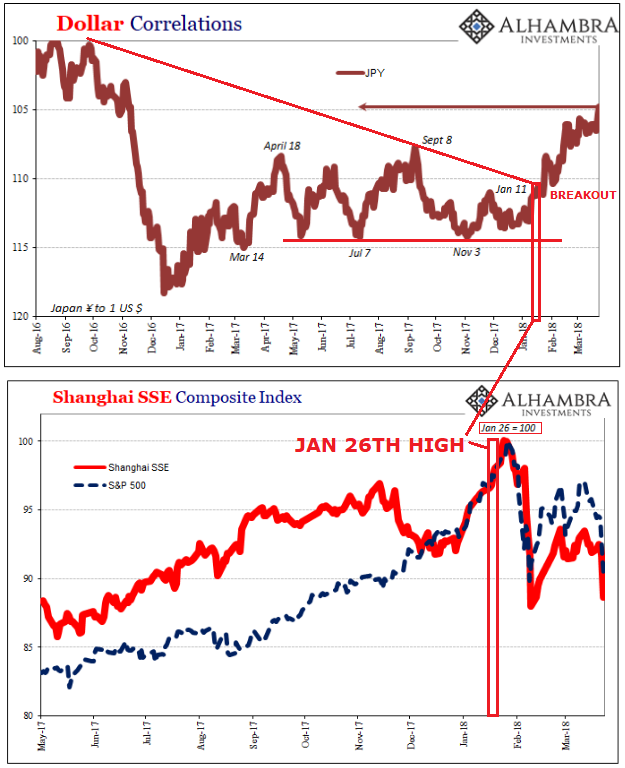

Since those global stock liquidations in late January/early February, European swaps have soured on the hysteria, not that they were all that impressed to begin with. Derivatives traders were betting then for inflation of merely 1.45% in early 2019 (if that was your basis for it, how can it have been anything other than textbook madness?) As of today, according to Bloomberg, they’re back down at 1.26%.

Sluggish price growth across the euro area looms, challenging Mario Draghi’s plan to curtail monetary stimulus while giving bond bulls a lucky break.

That’s the message from the underbelly of fixed-income markets that suggests the inflation trajectory across the the 19-nation region is not only easing over the next year but for the coming decade too. [emphasis added]

Maybe bond bulls (I despise that term; there’s nothing good about persistently low interest rates) aren’t lucky? What the second paragraph describes is, basically, more of the same no-growth world as we’ve been trying to live with for more than a decade. In Europe, as everywhere else, that’s been trouble no amount of QE or ECB for that matter seems able to cure. It gets worse with time, especially factoring so many false starts like this last one.

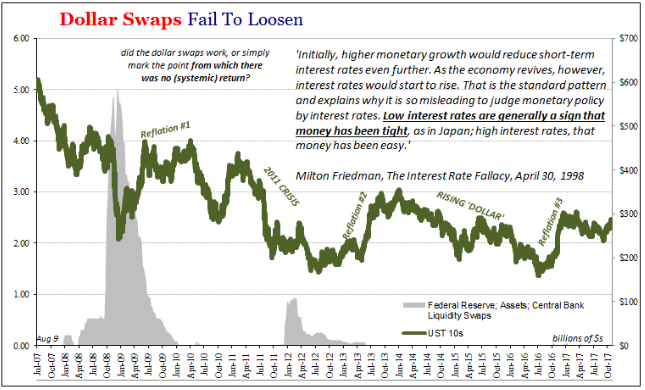

The greatest achievement for central banks has been to erase common sense, and the references to it which were once a steady part of economics. Low rates are stimulus, they claim, yet that’s not what they are at all. It used to be more widely understood (outside of Keynes) that persistently high bond rates (during the Great Inflation) suggested inflation, while stubbornly low ones indicated the opposite.

Thus, not only do bond markets indicate there is a problem they also handily describe exactly what it is.

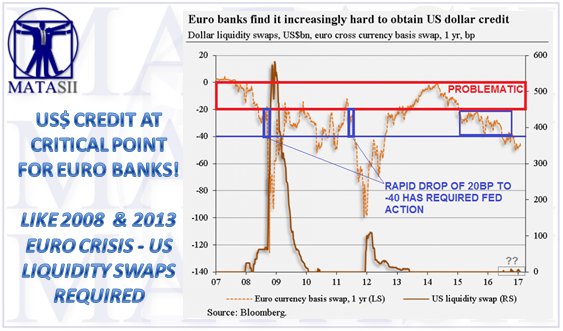

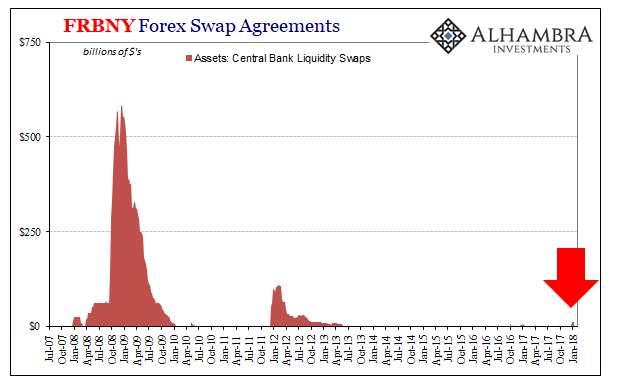

At the end of last December, FRBNY reported a little over $12 billion had been drawn on the Federal Reserve’s standing swap lines. These are the same as had been instituted with the various central banks around the world in the emergency(ies) of 2007 and 2008; made permanent in the early aftermath (re-crisis).

That amount, $12 billion, isn’t really all that much. It seems practically insignificant given the scale of especially the FX market where trillions in funding takes place every week. Still, that amount should be zero week in and week out. There is, outwardly, no reason why any foreign bank would be petitioning their local central bank for dollar liquidity.

These are not Federal Reserve policy instruments. They are standing agreements that are delivered by foreign central banks (collateralized by those central banks swapping local currency for the dollars drawn, with each giving cover to FRBNY in terms of any exchange risk) who also set the terms. They are, as they should be, collateralized between the bank borrower and overseas central bank with whatever paper that local authority accepts as eligible, meaning credit risk remains entirely there.

In looking more closely at the swap figures, two things stand out. The first is the pattern. The draws are for the most part clustered around quarter- and year-end. The second is the retreat of Japan from them, and the rise of Europe in its place.

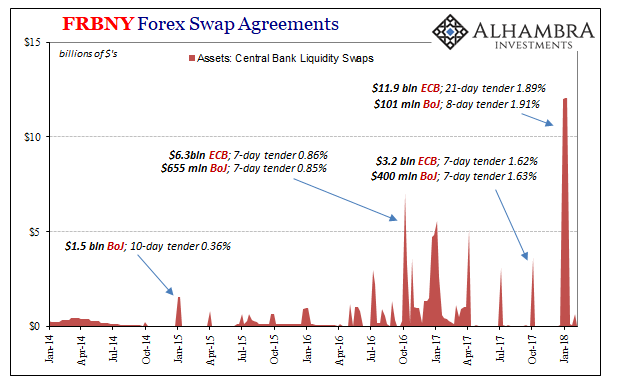

At the end of CY 2013, there were almost zero draws on dollar swaps. The ECB had tendered $272 million with an 84-day maturity in mid-December 2013, but apart from that there was just $1 million at year-end with BoJ (almost surely a test transaction).

Moving forward a year, the last week in December 2014 saw only the BoJ draw a significant $1.5 billion. In December 2015, there was again the ECB’s 84-day offer taking up $925 million and nothing from BoJ.

Starting in later 2016, however, things get a little more interesting. In the first week of October, not the last week in September, dollar swap draws totaled a combined $7 billion, most from Europe but still a noticeable proportion coming from Japan. The Chinese were on holiday that week.

This pattern repeated throughout much of 2017 until the largest use at the end of December. In that particular week, there was very little offered/demanded from Japan, leaving almost all funding heading into Europe.

The fact that these are almost entirely bunched at quarter-ends (or Chinese holidays) suggests more window dressing than perhaps systemic threat. But that, too, proposes significant imbalances somewhere. Why would any Japanese or European firm bid for well-above average cost dollar funding at these particular points? Either the market isn’t supplying it, or these particular firms are those undertaking the window dressing (meaning they are over-leveraged in between). In each case, it adds up to the same context.

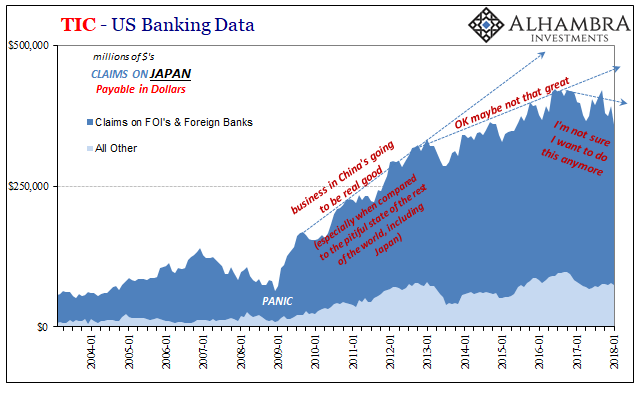

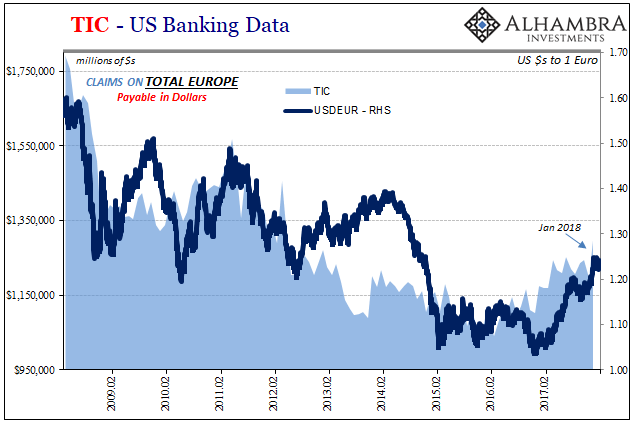

The reduced participation of Japan over time during this “rising dollar” plus “reflation” period matches other data and interpretations. They want out of the dollar redistribution business, and that it shows up here in an almost outside indication of strain seems perfectly consistent with both that intent as well as the reason for retreating.

Similarly, the growing balances running through the ECB and therefore Europe likewise indicate what we have suspected about eurodollar changes in Japan’s growing absence. The European banks have picked up some of the money dealing slack. The question for that $12 billion, and more so what’s happened since late January, is whether or not they wish they hadn’t.

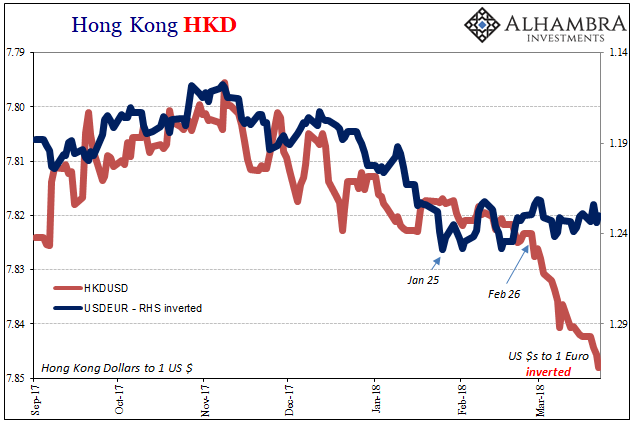

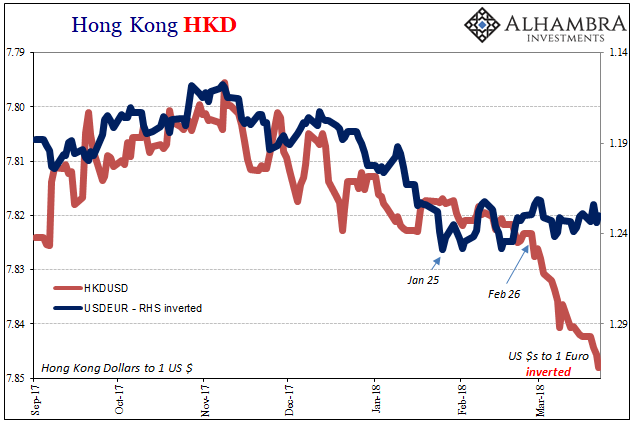

If you had dipped back into providing “dollars” largely to Asia (HK) last year, but now regret your decision, what could you do to offset perceived rising risks (including liquidity)? One thing you might do is hedge for deflation, meaning betting that inflation hysteria not just dies out but actively reverses (and continues to stay that way for a very long time).

Unlike conventional “wisdom”, the bank desks that are trading these things realize the direct connections between liquidity risk, low bond rates, and a global economy that can’t ever seem to achieve significant enough acceleration. The increased draw on dollar swaps at the end of last year don’t propose panic and a crash, but they do signal the same old global dollar problems – as well as add some good corroborative evidence on the geography of them. These were supposed to have completely disappeared last year, for what would have inflation hysteria otherwise been about?