Collateralized Loan Obligations Report Highlights

- Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) have many investor-friendly structural features, a history of strong credit performance, and characteristics that seek to provide protection in a rising interest-rate environment

- Historically, CLOs have experienced fewer defaults than corporate bonds of the same rating, a testament to the strength and diversity of the underlying bank loan collateral

- Guggenheim Investments' combination of credit research, structuring, technology, and legal expertise makes us particularly well positioned to capitalize on the attractive relative value of CLOs

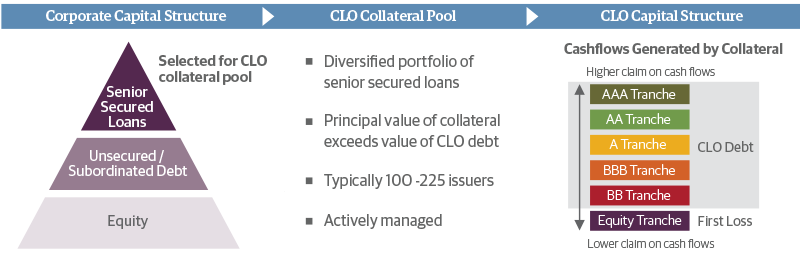

A CLO is a type of structured credit. Structured credit is a fixed-income sector that also includes asset-backed securities (ABS), residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). CLOs purchase a diverse pool of senior secured bank loans made to businesses that are generally rated below investment grade. First lien bank loans, which comprise the bulk of the underlying collateral pool of a CLO, are secured by a debtor’s assets and rank first in priority of payment in the capital structure in the event of bankruptcy, ahead of unsecured debt. In addition to first lien bank loans, the underlying CLO portfolio may include a small allowance for second lien and unsecured debt.

CLOs use funds received from the issuance of debt and equity to acquire a diverse portfolio of senior secured bank loans. The debt issued by CLOs is divided into separate tranches, each of which has a different risk/return profile based on its priority of claim on the cash flows produced by the underlying loan pool. Exhibit 1 sets forth the securitization process, whereby the senior secured bank loans from a diverse range of borrowers—typically 100 to 225 issuers—are pooled in the CLO and actively managed by the CLO manager. Economically, the CLO equity investor owns the managed pool of bank loans and the CLO debt investors finance that same pool of loans.

Exhibit 1: Understanding the Typical Structure of a CLO

Senior secured bank loans from a diverse range of borrowers—typically 100 to 225 issuers—are pooled in the CLO and actively managed by the CLO manager. Each CLO tranche has a different priority of claim on cash-flow distributions and exposure to risk of loss from the underlying collateral pool. Cash-flow distributions begin with the senior-most debt tranches of the CLO capital structure and flow down to the bottom equity tranche, a distribution methodology that is referred to as a waterfall.

Source: Guggenheim Investments. Collateral pools for most CLOs also have a small allowance for second lien and unsecured debt.

Each CLO tranche has a different priority of claim on cash-flow distributions and exposure to risk of loss from the underlying collateral pool. Cash-flow distributions begin with the senior-most debt tranches of the CLO capital structure and flow down to the bottom equity tranche, a distribution methodology that is referred to as a waterfall. The cash-flow waterfall, in connection with performance-based tests, provide varying degrees of protection to the CLO’s debt tranches. The most senior and highest-rated AAA tranche has the lowest yield but enjoys the highest claim on the cash-flow distributions, and is the most loss-remote. Mezzanine tranches pay higher coupons but are more exposed to loss and have lower ratings. The most junior tranche, equity, is the most risky, is not rated, and does not have a set coupon. Instead, the equity tranche represents a claim on all excess cash flows once the obligations for each debt tranche have been met.

CLOs are actively managed, meaning that the manager of a CLO can buy and sell individual bank loans for the underlying collateral pool in an effort to create trading gains and minimize losses from deteriorating credits. In addition, most CLOs are not mark-to-market vehicles and have extremely high hurdles to meet before collateral liquidation is triggered, making them better equipped to withstand market volatility.

The Collateral and Structure of CLOs Contribute to Strong Historical Credit Performance

The perception exists among some investors that all structured credit is riskier than more traditional fixed-income sectors. Partly to blame for this is CLOs' association with other forms of structured credit, such as certain types of mortgage-backed securities, which were at the epicenter of the 2008 financial crisis. Historical evidence, however, tells a much different story for CLOs. According to Standard & Poor's, CLOs experienced significantly lower default rates than corporate bonds between 1994 and 2013 (see Exhibit 2). In fact, AAA and AA-rated CLO tranches have never experienced a default or loss of principal, even during the depths of the financial crisis. CLOs’ historically lower default rate holds true across the ratings spectrum. CLOs' credit strength is derived from a combination of the high-quality underlying collateral and the structural features integral to CLOs.

Exhibit 2: S&P CLO Tranche Defaults vs. Corporate Default History (Cumulative)

According to Standard & Poor's, CLOs experienced significantly lower default rates than corporate bonds. In fact, AAA and AA-rated CLO tranches have never experienced a default or loss of principal, even during the depths of the financial crisis.

| U.S. CLO Default Rate | U.S. Corporate Default Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 - 2013 | 5 YR | 10 YR | 15 YR | |

| AAA | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 1.3% |

| AA | 0.0% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| A | 0.5% | 0.8% | 2.1% | 3.2% |

| BBB | 0.3% | 2.4% | 5.3% | 7.6% |

| BB | 1.7% | 9.2% | 16.7% | 20.5% |

| B | 2.6% | 21.4% | 29.9% | 34.1% |

Source: Standard & Poor's Rating Services "Twenty Years Strong: A Look Back At U.S. CLO Ratings Performance From 1994 Through 2013." Default rate = number of ratings that had ratings lowered to D divided by the total number of ratings.

Bank loans, a CLO’s underlying collateral, are senior secured loans made to businesses that are generally rated below investment grade. As a result of bank loans’ senior secured status, they contribute to CLOs’ attractive risk profile. CLOs have historically experienced lower default rates, higher recovery rates, and lower credit volatility relative to high-yield corporate bonds. Furthermore, the principal value of a CLO’s underlying bank loan pool exceeds the total principal value of the notes issued by the various CLO debt tranches. This concept is called "overcollateralization" and is one of the structural defenses that may provide some protection to CLO investors from risk of loss.

The structure of CLOs also contributes to the historically low default rate. CLOs face a series of coverage tests to help ensure the cash flows generated by the underlying bank loan collateral meet the distribution obligations in the various CLO tranches. One such test is an overcollateralization test, which ensures the principal value of a CLO’s underlying bank loan pool exceeds the total principal value of the notes issued by the various CLO debt tranches as long as the CLO debt remains outstanding. If the principal value declines below the overcollateralization test trigger value, cash will be diverted away from equity and junior CLO tranches toward senior debt tranche investors.

For example, consider a CLO created with $500 million of principal promised to the owners of its various debt tranches. To meet this $500 million obligation, investors and rating agencies may require that the CLO manager use the capital raised from the CLO’s debt and equity issuance to purchase $625 million of bank loans. This would result in an overcollateralization ratio of 1.25. In practice, each CLO debt tranche has its own targeted overcollateralization ratio. The overcollateralization ratios for each tranche act as covenants and, when tripped, redirect cash flows to purchase additional bank loan collateral or repay the senior-most CLO debt tranche.

CLOs are also subject to a variety of other tests that act in concert to protect debt investors from loss. Examples of these tests include a measurement of the industry diversification in the underlying collateral pool of bank loans, and the CLO’s exposure to non-senior secured loans. Other tests consider the diversity of borrowers underlying each CLO and set single obligor limits. There are also limitations on the amount of CCC-rated debt that can be included in the underlying collateral pool, which helps contain negative credit drift.

Post-crisis CLOs feature numerous additional credit improvements compared to their pre-crisis counterparts.

Finally, while CLOs exhibited strong and resilient credit performance during the financial crisis, post-crisis CLOs feature numerous additional credit improvements compared to their pre-crisis counterparts. First, rating agencies now require that CLOs feature substantially more overcollateralization than their pre-crisis counterparts. Second, where pre-crisis CLOs were able to make limited investments in subordinated bonds and other CLO debt instruments, post-crisis CLOs are collateralized solely by senior secured bank loans. Lastly, post-crisis CLOs' documentation is much more investor friendly, shortening the trading period during which the manager is able to actively manage the loan portfolio, and limiting extension risk for CLO securities.

The CLO Illiquidity Myth

While virtually all investment types are liquid in stable markets, the ongoing liquidity of the same investments in volatile markets depends on the leverage of market participants, market depth, and creditworthiness of those investments. Despite the relatively attractive risk-adjusted return characteristics of CLOs and the demonstrated credit performance of CLO investments, many investors question the potential liquidity of CLOs during periods of market volatility. We understand that the crisis-era experience is responsible for these liquidity concerns, but the structured credit investor base and marketplace scarcely resemble those of the pre-crisis era.

The pre-crisis structured credit market was dominated by highly leveraged investors, including structured investment vehicles (SIVs), Wall Street balance sheets, and hedge funds. The widespread use of leverage created an unstable marketplace, in which sellers were often compelled to purge risk assets to meet margin calls. Additionally, many of these market participants relied solely on rating agency risk assessments, instead of undertaking their own credit work. Finally, many of these highly leveraged investors, including SIVs, relied upon short-term funding sources to finance the purchase of long-dated assets. When access to short-term funding abruptly disappeared during the financial crisis market volatility, the investor base was unable to cope. The combination of these factors resulted in a highly leveraged and imbalanced marketplace that was unable to absorb and accommodate the reallocation of risk from the margin-called sellers to an informed and opportunistic buyer base.

The structured credit marketplace has evolved significantly since the crisis. First, the CLO market grew from a post-crisis trough of $263 billion to $426 billion as of Dec. 31, 2016. Second, the buyer base in structured credit has transformed from highly leveraged, fast-money traders to long-term asset managers, insurance companies, and pension funds. According to research by Citigroup, asset managers comprised 17.9 percent of the U.S. AAA CLO market at the end of 2016, a significant increase from 4.4 percent in 2013. This evolution is the result of regulations that prohibit Wall Street banks from operating proprietary trading desks, lack of demand for leveraged SIV vehicles, and the shrinking popularity of hedge funds. Today's institutional buyer base has created a durable sponsorship for structured credit that is not prone to the same leverage-based selling pressure experienced during the crisis.

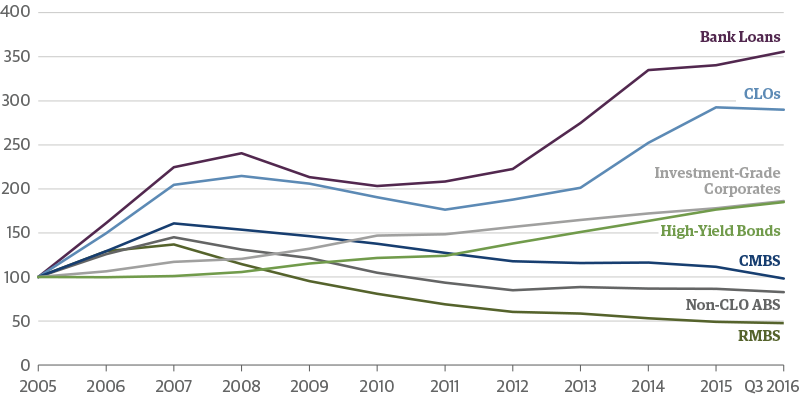

Exhibit 3: CLOs and Bank Loans Outpace Growth of Other Fixed-Income Sectors

Today's institutional buyer base has created a durable sponsorship for structured credit that is not prone to the same leverage-based selling pressure experienced during the crisis. The result has been growth in bank loans and robust new issuance in commercial ABS following the crisis, in stark contrast to the decline in non-prime RMBS.

Growth of Fixed-Income Sectors; Index 2005 = 100

Source: SIFMA, Wells Fargo, Credit Suisse, Guggenheim Investments. Data as of 9.30.2016.

Finally, the transformation of the structured credit investor base has been accompanied by a greater investor credit rigor. Long-term, real-money investors require a detailed understanding of credit exposure, compared to more flow- and momentum-based traders. These real-money investors have broadly taken note of the strong and resilient performance of CLOs and other commercial ABS during the credit crisis. The result has been broad sponsorship of the sector and robust new issuance in commercial ABS following the crisis. As illustrated by Exhibit 3, the CLO market has nearly tripled in size since 2005. This phenomenon contrasts starkly with the experience in less creditworthy products. Subprime RMBS, the worst-performing credit sector during the crisis, has seen its market size shrink by half since 2005 and has seen virtually no new issuance since the crisis. CMBS, also an underperformer during the crisis, has observed an extraordinary revision in underwriting quality and dramatic increase in investor protections such as credit enhancement.

We believe the transformation of the investor base from fast-money traders to real-money investors will provide liquidity to CLOs and other forms of structured credit during periods of volatility. The evolution of the investor base, the significant decrease in leverage, and the demonstrated creditworthiness of CLOs, collectively represent a significant evolution from the unstable pre-crisis markets and will provide a solid foundation for the liquid and orderly transfer of risk if and when market volatility returns.

Assessing Relative Value in CLOs

Core fixed-income investors continually evaluate current and prospective market conditions and assess relative value across a range of asset classes when making portfolio allocation decisions. A portfolio manager’s job is to construct a portfolio that is designed to deliver compelling returns in a wide range of outcomes. As these outcomes materialize, managers look to different sectors to perform in different ways to contribute to overall performance. The task of assessing relative value—pricing the risk and reward of possible investments—occurs within the context of a portfolio’s overall asset allocation structure.

We have found that CLOs generally pay a spread over their benchmark—typically three-month Libor—that is attractive relative to other securities with similar ratings.

CLOs have a number of features that make them an integral component of Guggenheim’s fixed-income mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, and institutional portfolios. In addition to their investor-friendly structural protections and credit performance, one of the most important characteristics of CLOs is their floating-rate coupon. CLOs’ floating-rate coupons help defend investors against loss in a rising interest rate environment. Fixed-rate securities, as with most government and corporate debt, decline in value as interest rates rise, and investors discount the value of fixed-rate bonds' relatively less attractive coupons. However, the coupons on floating-rate securities like CLOs adjust based on the current short-term interest-rate environment. As a result, floating-rate securities’ prices tend to be more stable in rising interest-rate environments than those of their fixed-rate counterparts.

Investing in CLOs is not without risk. As with other securities, CLOs are subject to credit, liquidity, and interest-rate risk, but the specific structure of CLOs means that investors must also understand the waterfall mechanisms and protections as well as the terms, conditions, and credit profile of the underlying loan collateral. Thus, the relative value determination for a CLO is not only its potential return relative to other fixed-income sectors, but also its pricing relative to other short-duration options, and relative to the amount of risk in the security. At Guggenheim, we have found that CLOs generally pay a spread over their benchmark—typically three-month Libor—that is attractive relative to other securities with similar ratings.

To capture opportunities in the CLO market, investment managers need the expertise to perform rigorous bottom-up research on individual bank loans in the underlying collateral pool. Some CLOs have as many as 225 issuers in their collateral pools. Accordingly, investment managers must have significant corporate credit research capabilities to fully evaluate the underlying credit risk in each CLO.

At the same time, the importance of understanding a CLO’s structural characteristics cannot be underestimated. Two CLOs with the identical collateral assets may produce varied performance due to structural differences. Additionally, the legal documentation that governs a typical CLO can be in excess of 300 pages. So while CLOs can offer compelling relative value, investors require the appropriate mix of credit research, structuring, and legal expertise to effectively capitalize on this market opportunity.

CLOs' Attractive Risk and Return Characteristics

With strong structural protections and historically low default rates, CLOs currently offer attractive spreads without assuming undue credit risk. Given the floating-rate nature of their coupon payments, CLOs are well positioned for a rising interest-rate environment. So why don’t more fixed-income strategies include higher allocations to CLOs?

Part of the reason is the stigma associated with the structured credit asset class as a result of the losses suffered by mortgage-backed securities in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Other investors avoid CLOs due to outdated perceptions about liquidity. Another factor is a lack of expertise in evaluating CLO investments. Successful investing in CLOs requires extensive credit research, structuring, and legal capabilities.

Important Information and Disclosures

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Basel III: Reform measures intended to enhance the regulation, supervision and risk management of the banking industry.

Basis Point: A unit of measure used to describe the percentage changes in the value or rate of an instrument. One basis point is equivalent to 0.01%.

First Lien: A security interest in one or more assets that lenders hold in exchange for secured debt financing. The first lien to be recorded is paid first.

Libor: A benchmark rate that some of the world’s leading banks charge each other for short-term loans. LIBOR stands for ‘London Interbank Offered Rate.’

Libor Floor: Ensures that investors receive a guaranteed minimum yield on the loans in which they invest, regardless of how low the LIBOR benchmark rates falls.

Mark-to-Market: A measure of the fair value of an asset or liability, based on current market price.

Mezzanine Financing: A hybrid of debt and equity financing that is typically used in the expansion of existing companies.

Second Lien: Debts that are subordinate to the rights of more senior debts issued against the same collateral or portions of the same collateral.

Structured Investment Vehicles: Pools of investment assets that attempt to profit from credit spreads between short-term debt and long-term structured finance products such as asset-backed securities.

Tranche: Related securities that are portions of a deal or structured financing, but have different risks, return potential and/or maturities.

Volcker Rule: Prohibits banks from proprietary trading and restricts investment in hedge funds and private equity by commercial banks and their affiliates.

Waterfall: A hierarchy establishing the order in which funds are to be distributed.

DISCLOSURES

The material herein has been prepared for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product.

Overview: What Are Collateralized Loan Obligations?