|

FED IS PREPARED FOR HIGHER SHORT TERM INFLATION?

FED’S POLICY: ‘AVERAGE INFLATION TARGETING’ (AIT)

By adopting average inflation targeting, the Fed is communicating that 2 percent is not a ceiling for inflation and that it may let inflation exceed 2 percent modestly and temporarily to make up for past low inflation. The key aim of this policy shift is anchoring inflation expectations. The basic idea is simple: Instead of aiming to return inflation over the medium term to the target rate of 2 percent, the Fed would aim to return the average of inflation over some period to the target rate.

What is considered an acceptable level of inflation? Answer: Around 2 percent.

-

- The Federal Reserve has not established a formal inflation target, but policymakers generally believe that an acceptable inflation rate is around 2 percent or a bit below.

- Academics within the Federal Reserve believe very low inflation usually signals demand for goods and services is lower than it should be, and this tends to slow economic growth and depress wages. This low demand can even lead to a recession with increases in unemployment – as we saw a decade ago during the Great Recession

- The UK, as an example, adopted inflation targeting in 1992 following a painful currency devaluation. The Bank of England was given responsibility for setting interest rates in 1998 with an inflation target of 2.5%. The Fed, which for a long time worked to a target range of inflation, adopted a fixed 2% target in 2012.

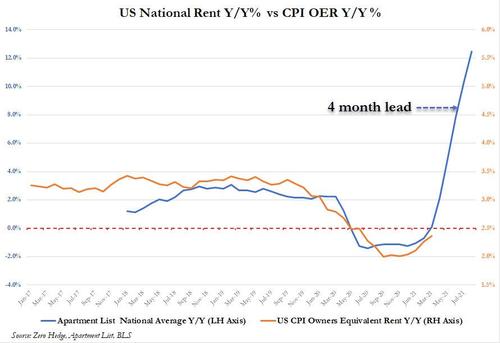

US core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, is likely still to be near 4% by year’s end. Macro policies, too, are likely to remain loose, judging by the Biden administration’s stimulus plans and the likelihood that weak eurozone economies will run large fiscal deficits even in 2022. And the European Central Bank and many other advanced-economy central banks remain fully committed to continuing unconventional policies for much longer. Although the Fed is considering tapering its quantitative easing (QE), it will likely remain dovish and behind the curve overall.

Like most central banks, the Fed has been lured into a “debt trap” by the surge in private and public liabilities (as a share of GDP) in recent years.

|