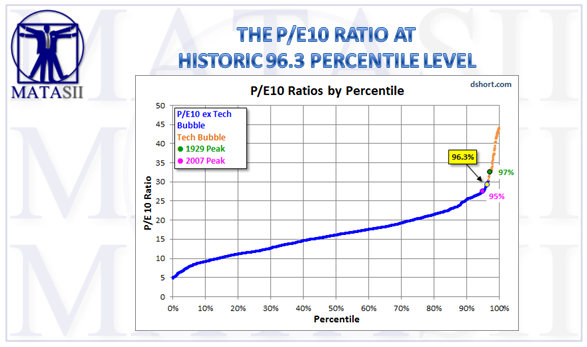

THE P/E10 RATIO AT HISTORIC 96.3 PERCENTILE LEVEL

--SOURCE:

The P/E10 Ratio

Legendary economist and value investor Benjamin Graham noticed the same bizarre P/E behavior during the Roaring Twenties and subsequent market crash. Graham collaborated with David Dodd to devise a more accurate way to calculate the market's value, which they discussed in their 1934 classic book, Security Analysis. They attributed the illogical P/E ratios to temporary and sometimes extreme fluctuations in the business cycle. Their solution was to divide the price by a multi-year average of earnings and suggested 5, 7 or 10-years. In recent years, Yale professor and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller, the author of Irrational Exuberance, has popularized the concept to a wider audience of investors and has selected the 10-year average of "real" (inflation-adjusted) earnings as the denominator. Shiller refers to this ratio as the Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio, abbreviated as CAPE, or the more precise P/E10, which is our preferred abbreviation.

The Correlation between Stocks and Their P/E10

As the chart below illustrates, the P/E10 closely tracks the real (inflation-adjusted) price of the S&P Composite. In fact, the detrended correlation between the two since 1881, the year when the first decade of average earnings is available, is 0.9977. (Note: A perfect positive correlation would be 1 and the absence of correlation would be 0).

The historic P/E10 average is 16.7. After dropping to 13.3 in March 2009, the ratio rebounded to an interim high of 23.5 in February of 2011 and then hovered in the 20-to-21 range. It began rising again in late 2013 and hit an interim high of 27.0 in August of 2015. It is currently at its interim high of 29.2.

Of course, the historic P/E10 has never flat-lined on the average. On the contrary, over the long haul it swings dramatically between the over- and under-valued ranges. If we look at the major peaks and troughs in the P/E10, we see that the high during the Tech Bubble was the all-time high above 44 in December 1999. The 1929 high of 32.6 comes in at a distant second. The secular bottoms in 1921, 1932, 1942 and 1982 saw P/E10 ratios in the single digits.

The chart also includes a regression trendline through the P/E10 ratio for the edification of anyone who believes the price-earnings ratio has naturally tended higher over time as markets evolve. The latest ratio is 51% above trend, unchanged from last month.

Where does the current valuation put us?

For a more precise view of how today's P/E10 relates to the past, our chart includes horizontal bands to divide the monthly valuations into quintiles — five groups, each with 20% of the total. Ratios in the top 20% suggest a highly overvalued market, the bottom 20% a highly undervalued market. What can we learn from this analysis? The Financial Crisis of 2008 triggered an accelerated decline toward value territory, with the ratio dropping to the upper second quintile (from the bottom) in March 2009. The price rebound since the 2009 low pushed the ratio back into the top quintile, hovered around that boundary and has now moved higher.

A cautionary observation is that when the P/E10 has fallen from the top to the second quintile, it has eventually declined to the lowest quintile and bottomed in single digits. Based on the latest 10-year earnings average, to reach a P/E10 in the high single digits would require an S&P 500 price decline well below 1000. Of course, a happier alternative would be for corporate earnings to continue their strong and prolonged surge. If the 2009 trough was not a P/E10 bottom, when might we see it occur? These secular declines have ranged in length from over 19 years to as few as three.

Percentile Analysis

We can also use a percentile analysis to put today's market valuation in the historical context. As the chart below illustrates, latest P/E10 ratio is approximately at the 96th percentile of this series.

Deviation from the Mean

Here are a pair of charts illustrating the historic P/E 10 ratio from its mean (average) and geometric mean with callouts for peaks and troughs along with the latest values.

Relative to the mean, the market remains quite expensive, with the ratio approximately 75% above its arithmetic mean and 89% above its geometric mean.